The following is a conversation with artist, writer, and multidisciplinary designer, Max Fertik, about his dis/assembly chair series, a project he developed during his Masters of Industrial Design degree at the Rhode Island School of Design in 2022.

CD: One of the first things you shared with me when we first spoke about your dis/assembly chair project was that you see the chair as a sort of design meme. What exactly did you mean by this?

MAX: I can’t recall who said it first, but I stand by the idea that the chair is nothing short of an icon. The possibilities are endless. We will never have a shortage of sexy and uncomfortable chairs. People love to hate on them, too, especially the “uncomfortable” ones. But when has anything that simply served its initial purpose been enough for designers? Essential things like food and shelter have always been chances to push aesthetic boundaries, and the chair just one example.

When I say meme, I mean it both in the satirical and the iconic sense. To make a chair is a testament to a designer's ability to make a structural object, but equally something that every designer secretly wants to make. Every famous architect, from Koolhaas to Lina Bo Bardi has designed a chair, and these always feel like a little taste test for their style. What would happen if every chef or accountant made a chair? What would your landlord’s chair look like?

Chairs are a shared obsession. Go on instagram and you’ll find countless accounts solely dedicated to posting the endless permutations of the chair. So when I say meme, I mean it in the most complimentary sense—that the need to make a four-legged seating object that is unique is like writing the perfect song. It’s a game of necessity and comfort that plays with how far we can stray from a functional tool for seating. A chair is so much more than that. It’s (literally) a platform for every maker to stake their claim to this agent of culture. And so on...

CD: When I first stumbled on your dis/assembly chairs, I was immediately attracted to how flat they were. How did this form emerge? Did it come from a particular process? And is flatness an important part of the chairs’ function, or was this simply an aesthetic choice?

MAX: This project began with me forcing myself to create an “Industrial Design” and I’m still unclear if I succeeded at that. Part of my program, aside from being a place for unending questioning, was to create something commercial, something that could sell. So instead of inventing something new, I looked at the objects that have always worked. I got really into what it meant to be ordinary, specifically the type of ordinary described in the book, “Supernormal: Sensations of the Ordinary” by Jasper Morrison and Naoto Fukasawa. These designs were so ubiquitous they’re almost uncanny. Think Moka Pot, Post-Its, the rubber flip flop, and the chair that comes to mind when someone says “chair.” The whole idea was to investigate what made those things normal, why we need to open our eyes to the ordinary, and discuss what it means for an object to be “timeless.”

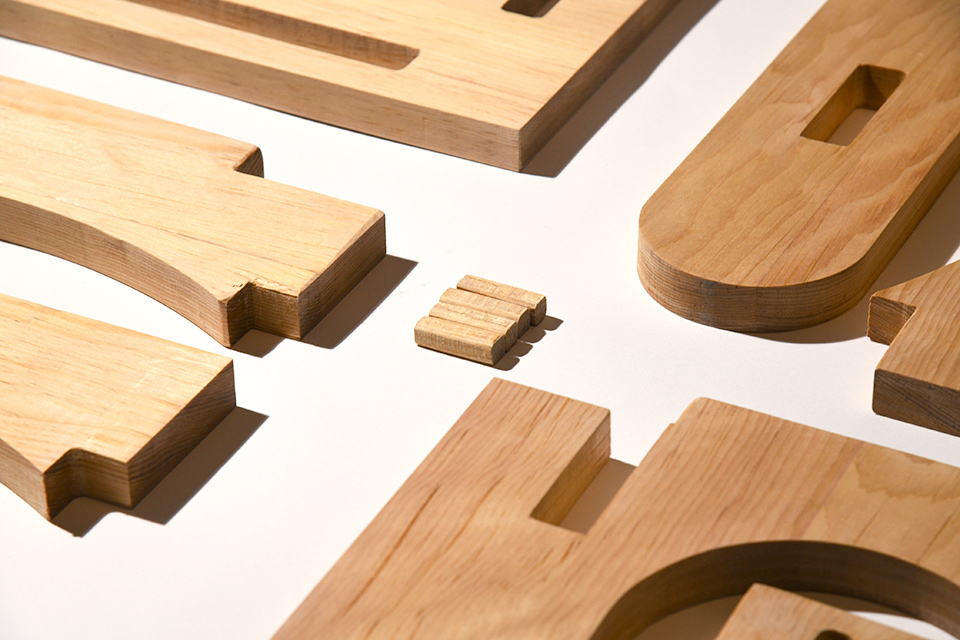

In this vein, I first wanted to design forty chairs. And I did! They could all be made very simply using a sheet of plywood and something to cut them out. This is why they are so flat. The one thing that these chairs had in common was their flatness, their ability to be cut from the same 4x4 sheet of plywood, with the modality of slotting them together with no glue or screws.

But making a “simple” design is often the hardest kind because in order to make it look simple, it has to work and it has to work well. So, I decided on two of my forty designs and tried them out as miniatures (which took several tries to get right). I made some 3D-printed versions as well. And finally, I built a couple plywood prototypes to make sure the chair made sense next to a human and that it could be assembled and disassembled intuitively. That was the hardest part. But I’ll come back to that.

The form of these chairs was derived from iteration. The only aesthetic I wanted was for these objects to look “normal” and function as chairs. The curves in the design were influenced by my instructor’s suggestion that an arch provided an efficient weight distribution, and the crossbars were put there to keep the chair from moving. Ultimately, this flatness and overall aesthetic form came from an attempt for these chairs to be easily made from a single sheet of wood. I was also interested in creating a spatial flatness that blends itself into a space and doesn't draw overdue attention to itself. This was of course the most radical part of it all.

CD: The name you gave to these chairs suggests they are designed to be taken apart and put back together again. This got me thinking about portable furniture (like beach chairs or folding tables), as well as mass-produced flat pack furniture that’s intended for home assembly by the general public. Is assembly and disassembly an important utilitarian feature of these objects, or are you more interested in this functionality as an idea?

MAX: To give you some context, my parents used to be antique dealers. They used to drag me all over Rhode Island to see different pieces of furniture they wanted to buy and sell. One of my favorite pieces was this chair for golfers that could fold up into a walking stick. Not really a flatpack example, but a very archaic transformer that has really stuck with me.

When I first started this project, the first prototype I made completely failed. In fact, it actually broke while I sat on it during my crit in front of my entire cohort. The horror! But it was a valuable lesson—embarrassment is the greatest teacher.

The original idea for this project was that the chair would fold up into a wooden suitcase, and then easily unfold into a simple chair (not unlike a Jacob’s ladder toy). I was heavily influenced by Hennessy and Papanek’s Nomadic Furniture (another design meme), and their utopian vision of DIY reality. I even called this first version the Nomad Chair, leaving little to the imagination.

For the second iteration of the dis/assembly chair series, I used the incredible resource of the Rare Woods Collection at RISD and got 50 board feet of Sugarpine for free. The soft wood is famously strong and lightweight (it’s often used in Japan for construction), and it was perfect for this project.

This had me wonder why I ever bought any new materials when there is so much incredible trash lying around RISD. If I could make a silly chair from an old shipping crate (which I had done for a previous project), I wondered what else would be possible and decided to focus on using scrap materials as much as I could.

Now to get back to your question. At first I wanted this to be a chair that you could take apart and put back together over and over again. But as I began testing it with friends and faculty, I realized that I was more interested in the concept of dis/assembly rather than its actual functionality. Instead of taking the chair apart and putting it back together over and over again, you put it together once and the longer it stays assembled, the stronger it becomes. Wood grows and shrinks with the seasons, and the way these chairs were designed, they grow into themselves the longer the owner has them. The reality is that constant disassembly slowly weakens the object. On the other hand, slow, intentional assembly gains strength with time. No need for glue or screws when you’ve got time.

In a way, this is slow furniture. (or at least a response to fast furniture). Ultimately, this chair series is a flatpack manifesto that favors interaction and permanence.

CD: A few years ago, you made made a work in collaboration with Grace Carver called “fuck IKEA”. Can you tell me a little bit about that project and how it fits into the broader conversation you seem to be having (through the objects you make) with the mass-market furniture production model as a whole?

MAX: In many ways, this was my first serious design project (while at the same time it was anything but serious). I studied for a semester at Elisava School of Design in Barcelona as an undergraduate with zero design experience. Thankfully, I was paired with Grace, a design student from Melbourne, Australia, who unlike me, did know her shit. In this furniture design class we both took, our professor gave each group an Ivar IKEA chair (a classic Supernormal chair), and we had to make it into a “new” redesigned chair. Grace and I decided to make the anti-Ivar chair. We were interested in seeing how far we could stray from its original form and have it still be considered a chair.

We completely took the chair apart. We then suspended each of its deconstructed pieces in solid blocks of cement and stacked them on top of each other so that they vaguely resembled a four-legged chair again. It looked insane. It was reminiscent of a decaying or buried living thing slightly peeking out of the ground like a zombie pushing a hand out of a gravesite. At the time, the idea was to take a pristine, mass-produced chair and transform it into something more horrendous that challenged the user and made them think about the lifespan of their objects.

Today, I look back on this piece with a sigh and a salute. The “fuck IKEA” was never meant to be a “fuck you, IKEA,” it was more of an exclamation and a call for more honest opinions about inanimate objects. We wanted to give more intention to the objects we surround ourselves with as if they are a pet or a companion, things that will outlive us.

In reality, I actually love IKEA. I even wrote my Art History thesis on IKEA (a year after the fuck IKEA project), in which I discussed where IKEA fit into the decorative arts canon, and the ways the West uses design to give meaning to their lives. I think of IKEA showrooms where you can try on different interior identities like The Sims. I don't believe design can change the world, but I do think it should be fun at least.

CD: You also mentioned that you tend to make industrial design about industrial design. How does this project fit into your larger body of work, interests and preoccupations with material, manufacturing, form etc.?

MAX: I do try to make work that is critical of itself. I’ve also been sure to critique industrial design as a whole by trying to make work informed by its environment. But I have also made work that is about aging and the body, even a project about death and AI. I try to use my work as a way of engaging with material, practice, and ecosystems while sneaking around under the guise of a friendly designer. In other words, I have made an effort to make a wide range of things to prove that design and its language can be a performance too.

Coming to this discipline as a sculptor and researcher, I continue to see design as an outsider. While I can now say that I am a multidisciplinary designer, I am still at my roots an American artist, making work “about” something. In a similar way that my chair projects have dealt with design itself, my current work with future ecologies and post-industrial studies seeks to critique the way that mass manufacturing has created a system built on infinite growth and extraction that will eventually cave in on itself.

So in many ways, the fuck IKEA project was a harbinger of what was to come. It was a realization that the ways we have stolen, used, and disposed of land and resources have landed us in a place of disbelief. My body of work is concerned with material, manufacturing, and form, and how these are all ingrained in our soil, our water, our DNA, and how a shifting of value systems and a little imagination can go a long way.

In terms of my relationship with the industry and other makers, I hope to find my place as a designer with an affection toward conceptual art and research. I work with more artists than designers, but feel comfortable in a room talking to either. I hope to develop a practice that has both a functional and conceptual sect, both existing at the trade shows and the gallery. If I could exist somewhere in between I would be happy.

CD: What’s your favorite chair designed by someone else?

MAX: I think my favorite chair is Sesc Pompeia by Lina Bo Bardi. The darkness and simplicity is so haunting and connected to its materiality that it really exerts itself. The little notch at the top is so cute and the darkness reminds me of being alone in a forest.

CD: What are you reading, watching, thinking about these days?

MAX: Right now, I’m reading “The Wind Up Bird Chronicle” by Haruki Murakami which is both heart-wrenchingly depressing and incredibly addicting. It’s worth a read, if you dare. I am also currently reading “How to Make a Chair From a Tree” by Jennie Alexander. The author, who sadly passed away recently, is a trans woman woodworker who pioneered the two-slat post-and-rung shaving chair. It’s a very wholesome read, even if you’re not planning on making a chair from a tree.

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Max is a writer, designer, and maker whose work flows between the various languages of function and the material ecologies of the post-industrial age. He received a BA in Art History and Sculpture from Trinity College in 2019 and a Masters of Industrial Design from Rhode Island School of Design in 2023. He also taught a course at RISD about radical applications of design in 2022, and has shown in exhibitions internationally. His work with invasive species was most recently shown in the 2023 Venice Design Biennial. He worked as a studio assistant at FOS/Studio Grotta Nuova in Copenhagen, an artist in residence with Simon Johns Studio in Quebec, and was most recently editor in chief at RISD’s “volume 1” publication.

Max is currently working remotely as a designer for Altimeter Design Group, and teaching an afterschool Design/Build program with DownCity Design. In his spare time, he is 1/6th of an artist collective called “BAC” which makes floating wetland installations, and also does top secret invasive species recon with his partner Erika for their Somerson Sustainability and Innovation Fellowship.