In fall 2023, we paid a visit to artist, architect, and educator Markus Berger at the Repair Atelier, an art/design workshop in Providence, RI that investigates and activates ideas of reuse. The Repair Atelier was created by Markus as a collaborative space for rethinking and reusing discarded and broken objects with the goal of transforming not just the objects themselves but also the communities that form around them.

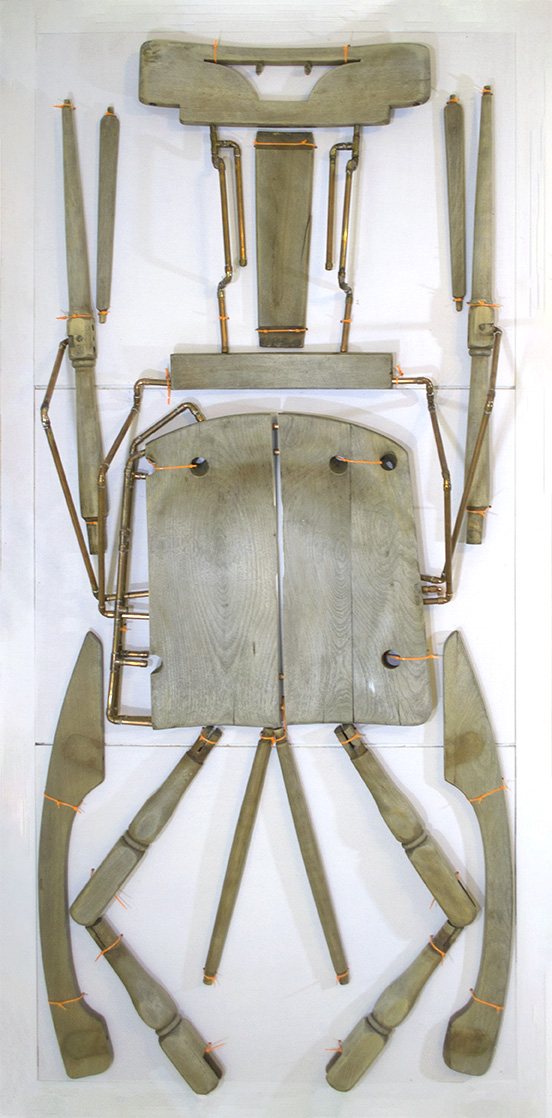

CD: The first time we visited you here at the workshop, we noticed those two chair skeletons hanging at the back of the room. While they’re deconstructed into individual parts, they’re still somehow recognizable as chairs. The way they’re arranged and mounted on these boards also makes them look uncannily like human skeletons. What are these objects? How did they come to be?

MB: These pieces were made at the very beginning when I first decided I didn’t want to work with buildings (and contractors, budgets, and clients) anymore, but instead wanted to pursue my own self-directed work. They came out of an investigative process to figure out how to take abandoned objects, thrown-away objects, and give them a new life.

In the process of repairing a broken wooden chair, I first unmake the chair in order to clean all the joints before putting them back together again. I was trying to do this with this one particular chair, and within this process of disassembly, I arranged all of the pieces very nicely on a table in my workshop.

The next day, when I walked back into the workshop, I imagined seeing parts of a body. I was kind of set back at first, but then I saw this opportunity—I discovered within these fragments of a chair that there is this resemblance of body parts. From there, I started rearranging the pieces in different ways and generating “divergent beings.”

Something that’s been important to me for some time, even prior to starting the Repair Atelier, was the idea of finding and breaking boundaries between (false) separations within art and design fields. Since I started teaching at RISD, I’ve been interested in breaking boundaries between art and design, breaking boundaries when it comes to what architecture should do (and certainly also what interior architecture should do). I’m also interested in breaking cultural boundaries, normative boundaries etc.

So when I saw these pieces of a chair lying on that table, I saw that they somehow “speak” chair, yet they are not “chair.” They bring up this ambiguity that I love to play and also teach with—an ambiguity that makes unclear what an object was and is, a blurring of its boundaries.

CD: I think these skeleton-like objects, these “divergent beings,” are quite interesting formally in that they contain within them a tension between an object (a chair) and the human body. They are chairs, but they feel human. And looking at them almost feels like looking at a head, arms, a body. They’re compelling, strange-looking objects.

MB: Part of this has to do with the way I arranged them. The skeletal arrangement exacerbates that. Maybe this was not necessary, and maybe I should think about removing or distorting them a little because it’s possible that the body is almost too literally involved here. That said, their human form was very important to me when I started this entire process.

CD: When did you make these?

MB: I originally made these in 2017 for an exhibition called “Remaking.” This was before my work was really focused on the concept of repair. At this time, there was a dean of Graduate Studies at RISD called Patty Phillips—she was a fantastic academic dean who brought artists and academics together to discuss this show at the finissage. During one of our conversations, she brought up the topic of “re-pairing” and the idea that repair is somehow about bringing things together again. This was, for me, the starting point of focusing my work and thinking on processes of repair, reparative thinking, and reparative practices as they’re now laid out in the book I worked on with Kate Irvin (head curator of textiles in the RISD Museum of Art).

CD: This leads to a question we have about the other chair objects here in the space. While most have the familiar form of chair-ness, many have been made unfamiliar through some sort of formal and material intervention. I see chair collages, chairs with holes drilled into them, chairs whose parts have been deconstructed and rearranged etc. You call these chairs “repaired objects,” which implies they were broken and have somehow been “fixed.” Can you share more about this ongoing project, and the philosophy that informs it?

MB: One thing I’m interested in is finding meaning and aesthetic value in the wounds, in the brokenness of things. I’m interested in seeing brokenness not as a bad thing that one has to fix, but in understanding brokenness as something that we can find potential in. Brokenness can bring us to a conclusion of our own self-being, both personally and as a society.

I was trained as an architect and worked in the context and mindset of typical 20th-century architecture. This was a world that aimed for “perfection” and held no space for the idea of brokenness. The dominant mentality was that as soon as something was broken, we had either to fix it (i.e. bring it back to the way it was when it was new), or throw it away.

When I was studying architecture in Vienna, I remember looking at and thinking about all the pristine new architecture around me. I was surrounded by beautiful buildings. But when it came to my own living space, and the bars and cafes I liked to go to, I realized I preferred the old ones, the shabby ones, the ones with smoky ceilings and broken objects. I liked the used furniture, not the new, fancy, glossy stuff.

This is when I started questioning the values and mentality of modern architecture. I realized that I no longer had an interest in fancy, shiny objects. I started consciously appreciating things that have a crack or a rip in them. Things that are visibly worn.

At this time, fashion was also becoming aware of this idea of wear, and people were running around with distressed or torn jeans. But I was more interested in the real distress, not the kind of manipulated brokenness designed into new objects to make them appear old. I wanted to see the real wear that happens to things naturally over time.

A few years ago, we had this wonderful colleague at RISD who is professor emeritus now called Yuriko Saito. She’s a philosopher who wrote a lot about the aesthetic of the imperfect. In the aesthetic of the imperfect Yuriko challenges the pursuit of flawless and standardized beauty, suggesting that there is a rich aesthetic experience to be found in the irregular and the incomplete. She prompts in her writing a reconsideration of our aesthetic values and invites us to find beauty in the often-overlooked aspects of the world around us. I learned a lot through conversations with her about how we look at the environment and the things we make.

Our Western obsession with the new and the shiny is not just a visual and philosophical problem, it’s also a material one. This way of thinking (this obsession with perfection and neglect of the things that already exist) is a large cause of all the trash that accumulates around us and that we export to the Global South.

Having worked and lived in places like Karachi, Pakistan, I have seen the effects of our 20th-century values and industrial achievements first-hand. These modernist ideals have benefitted a small part of the world’s population, but when you’re living in one of the countries that makes up the other larger part, you can actually see how these ideas and practices are questionable on a real, material level.

Many of my “repaired objects,” actively fight these modernist aesthetic values that I have been questioning for a long time.

CD: It’s disturbing to think of how much the Global North outsources our garbage. We don’t have to burn it in our backyard, we don’t have to dig our own holes for it. We have the luxury of dumping our trash somewhere else. This abstracts it, and makes it so invisible that we don’t need to confront the material reality of all the things we throw away. Someone takes away the trash and we never have to look at it again. It’s almost as if it dematerializes into thin air.

MB: And yet that doesn’t actually happen for most of the objects we produce. Dematerialization works when native Americans build buildings. Europeans still say there is no such thing as old architecture in America, but that’s a very particular (and incorrect) mindset because there always was pre-European architecture, it has just degraded back into the soil. The kind of circular thinking that native Americans had for ages is now being celebrated as this new idea of the circular economy. The problem is that we’ve invented all these materials that do not deteriorate. Many of these materials are toxic and they pollute our water, animals, and ourselves.

My work in Karachi (as well as Bangkok), has been about studying the informal sectors of the circular economy and the informal economies that take the trash of the West and process or transform it. I’ve also lived and worked in Berlin, which is a place where many people have already integrated the circular economy into their everyday thinking and lifestyles.

In this idea of the circular economy, you come in and try to give an object that would otherwise be thrown away a new life. This is what I’m teaching now in my department with buildings. While I have moved away from new architecture and instead looking at ways to transform existing buildings, I realize that the architecture field still loves (and is attached to) the appearance of the new.

For example, the building that we work in (the CIT building) has nothing old left in it that reminds us of the former building besides the floor, because everything is boarded up so that it looks perfect, so that it looks like a box. I argue that this is not a great environment for any type of creative work.

CD: So why is the chair so central to your practice? Why not lamps, toasters, bicycles?

MB:My process still involves thinking like I’m intervening in a building, but I’ve switched the scale of things down to an object. A chair is an object that doesn't require me to deal with clients and contractors. With an object (as opposed to a building), I can experiment more quickly instead of worrying about designing for someone or something in particular. Each object then becomes an object of study, of experimentation.

One aspect of the field I come from (of interior architecture) is the interior’s relationship to the body. My constant criticism of modern design and of modern architecture is the dissociation it has with the body. Modernism brings forward very particular aesthetic values that forget the body much of the time.

While I’ve experimented with other types of objects, the chair (besides apparel design), is for me the closest designed thing to the human body. I really want to engage with the topic of the human body, so that brings us back to the discussion about what I call the “divergent beings,” those human, creature-like chair bodies we were discussing earlier.

CD: We have some more questions about these “repaired objects,” these chairs we see all around us here. While it’s clear you’ve performed some degree of structural repair on each, your interventions go beyond the functional. You’ve collaged chairs together, sliced up different parts and rearranged them, inserted new materials into existing chairs etc. This begs the question, why are these interventions so obvious? How does this approach reinforce or enact your philosophy of the aesthetics of repair?

MB:As I said earlier, I’m not interested in bringing these objects back to their original condition. I’m not trying to fix them like the car in the garage that gets fixed and then afterwards, you don’t see what was broken. My goal is to bring forward into society an aesthetic of the imperfect and understand the past as a value of authenticity, of the narratives an object contains. I like finding objects, broken objects on the street. I pick them up and bring them into the workshop before knowing what to do with them. It’s always great to have these broken chairs around to look at and think about. This is a process that often takes months—I often sketch with them before I touch them or do any actual work on them.

Recently, I have organized my work on chairs into four categories.

One category we talked about already is the “divergent beings” which are those chair skeletons. Here, we have objects that are flattened out or separated into individual parts. These objects sort of of speak chair, but they clearly aren’t chairs. They’re not functional.

The other three categories fall into a borderline area between an object (a piece of functional furniture) and a sculpture (a piece that has the potential to bring forward discussion).

Within this area, one main category or approach is what I call “breaking monumental origins.” For me, this is about discourse about the monumental origins of Western European philosophy of architecture and design. It’s about fighting this Eurocentric idea that the 1920s produced the best design there is.

I think the way architecture and design were approached in the 1920s was correct for its time, but this mentality left us with the wrong values. One good example of “breaking monumental origins” is the Marcel Breuer Cesca chair here, the one with the steel frame. Its shiny, simple form and its materials (especially the tubular steel) express this obvious connection to an industrialist mindset in the 1920s.

But, I would argue, this chair leaves out the human body, and a diversity in materiality. What remains is just a statement of aesthetics and industrial values. So when I say “breaking monumental origins,” I’m aiming to break the values of 20th-century design by bringing back the messy body through many different forms, many different materials, and forms that somehow relate back to the body again.

So in this category, there’s a Marcel Breuer chair, there are chairs by Mies van der Rohe, there’s this classic Eames chair, all of the objects in this category are a chance for me to mess with the values of modern design.

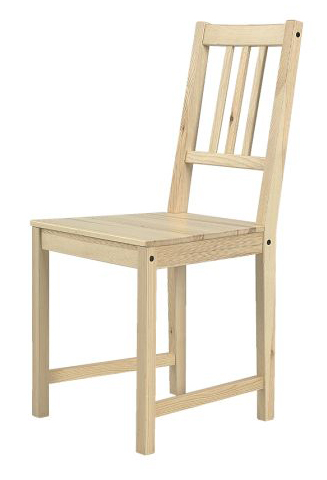

The third category of “repaired objects” is one I call “remaking the mundane.” Here, I work with chairs that are totally mundane, not very exciting, a little bit dull, and usually fast-produced. For example, there’s an IKEA chair hanging on the wall over there. It’s the orange one on the top left. That’s an IKEA Stefan chair that I found broken, wobbly, useless. It’s made from the cheapest kind of pine wood that exists.

I decided to approach this particular chair by bringing it into a circular system. I sliced up the thicker pieces and just took the material from the existing Stefan chair and re-coordinated it by triangulating the entire thing. I used a binding material to put it all back together. After all that, it’s still the Stefan chair (at least in terms of its material), but it has a totally different appearance, strength, and maybe even a different use. What this new object demonstrates is that one can (within the same materiality) recombine something that exists and transform it totally into something else.

CD: So when it comes to this repaired IKEA chair, you’re not actually bringing in any new materials into it, is that correct?

MB:That’s right. With this chair, there’s nothing new coming in besides the binding material that holds everything together.

I’ve also taken other approaches to “remaking the mundane.” For example, with the chair right below that one, I took the opposite approach. I took the side frames of five different chairs and pinned them together. This resulted in this messy collage of a chair that you see.

CD: So what is the fourth category of “repaired objects?”

MB:The fourth category I call “traditional rewriting.” Here, I take these very traditional chairs that need repair and I try to rewrite them in some way. I specifically dislike objects that were made when industrial processes started and designers tried to reappropriate the old, hand-carved chairs by copying the ornaments and making them cheaply using machines rather than making them by hand.

The wood chair up there on the wall is an example of this “traditional rewriting.” When you look at all the ornament in the chair’s legs, its form suggests a handmade object yet it was made using an industrial process. There was even more ornament in this chair when I found it, which suggested a connection to a more traditional chair, but this ornament was dishonest in a way. What I do is I try to take away some of these traditional elements and forms and do a sort of text edit on them. I edit out some of the ornament and edit out some of the aspects that are totally unnecessary in terms of the materials that were added on to make the chair look luxurious or older than it really is.

Another example of “traditional rewriting” is the other chair hanging next to it which was added to the collection early on in 2018. I’m referring to the Danish-looking wooden chair with the pink rope. This piece began as a traditional-looking Danish-style imitation chair. It had this broken and disgusting seat that I decided had to be widened as part of its transformation, so I sliced the chair in half and inserted these copper spacers in the center.

I like moving objects away from what they were originally supposed to be, supposed to look like. In order to work against myself as a trained architect and designer, I often work without a plan or sketch of any kind. So for this chair, I just started connecting this space between the frame in order to reconnect the chair in a way that allows someone to sit in it comfortably while creating this, complex-looking character.

I was quite brutal with the original version of this chair knowing that it was a reproduction trying to imitate modern Danish design. I wanted to mess it up in a way that distinguished between the original and my intervention. So I spaced it out with this copper piece that I mentioned earlier, and then drilled holes in the frame and added these pink cotton ropes that make the object into something totally different from what it was, what it stood for before.

CD: You mentioned this chair is comfortable and that you can sit in it. Do you care if people can sit comfortably in the chairs you repair? Is functionality important to you?

MB:That’s a good question. Since I always approach an object with a unique way of intervention, I have different goals for each. For the chair we’ve been talking about, there was certainly an improvement in seating because I widened it and allowed for more stabilization of the back. But there are maybe one or two chairs here that aren’t really meant for sitting. Like this one here, this strange collage of all these sides of chairs, it’s not very comfortable to sit on.

That said, mostly you can sit on these chairs. I do want all of these objects to have a kind of duality where they are still good chairs, but they’re hopefully something else as well.

CD: In many ways, this whole approach seems closer to an art practice than design, but your critique of mass production and waste does have some connection to movements in the 60s and 70s that pushed up against the genre of design that came out of industrialization and the modernist attitude. Ken Isaacs’ “Living Structures,” and Henessey and Papanek’s “Nomadic Furniture” are just a couple examples of this. These older projects were interested in finding alternatives in industrial design that were more imaginative, more empowering to the end-user, and potentially more sustainable than the dominant industrial models of the time. Do you think there is any value in reexamining some of these old utopian DIY movements as viable ways of thinking about design today?

MB: As I talked about earlier, the 1920s were a time when the big inspiration for designers came from industrial innovations. In the sixties, designers had their own unique set of issues. At this time, they talked about the movement of people and about nomadic life again, and some people were doing really interesting work which related particularly to the problems and ideas of the sixties.

For me, the most important of these is Victor Papanek who criticized industrial design and suggested that design might actually be making things worse for the planet and for people. He pushed up against this modernist belief that designers are in the business of fixing things, of making things better through design. Of course, if this were true, it would be the best possible definition of the designer.

But unfortunately, we produce stuff that just goes to waste. I think what Papanek did was show people what they could make on their own. I think this was important because we know that if people have invested time and energy and thought in something, they will value it more. This works against the effect of mass-manufactured products that are cheap and fast—they are not valued so their lifecycle from purchase to landfill is so much shorter.

That said, I think the 21st century has its own issues that are mostly related to the environment and the increasingly digital nature of our world. Our environmental issues are far beyond what we could have imagined in the sixties, and we are becoming increasingly distanced from the objects we use every day. Today, most of us don’t have any real relationship to the things around us, to how or where they were made, or where they go after we’re done with them.

CD: So, would you say then that the work you’re doing here is more about trying to get people to reimagine how we value the objects around us than trying to reinvent a new system of manufacturing?

MB: Yes. I am not thinking along the lines of manufacturing at all as my interventions are minimal, one-off craft interventions. Changing a capitalist-enforced mindset of habits and aesthetic values is hard. My goal to change societal culture almost impossible.

CD: So what are you working on or thinking about these days?

MB: I am thinking and writing about the process of unmaking and deconstructing in my work. Unmaking as a process of taking apart to understand the true form, the structure of things, the relationship between things—but also values, ideologies and histories—and as such, it is an interpretive process. My work on Repair is both a process of unmaking and remaking, and stands in opposition to the idea of the original, for it is re-making not to hold on to some lost past, not to mark continuity with the past.

CD: Markus, thank you so much for sharing your work with us.

MB: Thank you for coming and for the opportunity to have a chat with you.

CD: It was great. We really enjoyed it!

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Markus Berger is an artist, designer, writer, and Professor of Interior architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD), a registered architect (SBA) in the Netherlands, and founder and director of The Repair Atelier: an art/design workshop that investigates and activates ideas of reuse. His work, research, writing, and teaching critique the ethics, aesthetics, and values of modern architecture and focus on forms of change and repair in art, architecture, and design. Berger co-founded Int|AR, the Journal on Interventions and Adaptive Reuse (2009- 2019) which addresses such issues as preservation, conservation, alteration and interventions. His latest co-edited books are: Intervention and Adaptive Reuse: A Decade of Responsible Practice, (Berger, Wong), Birkhauser, 2021; and Repair: Sustainable Design Futures, (Berger, Irvin), Routledge, 2023.