Common Dimensions discovered Bill Carroll’s “Dust Chair” when it was on display at RISD’s Sol Koffler Gallery in early fall 2023. We caught up with Bill a couple months later to ask him about the chair, his design process, what inspires him, and how this object relates to waste, value, and the roles of chance, improvisation, and scarcity in generating new forms and ideas.

CD: Your “Dust Chair” has a very distinct formal quality that comes out of a particular approach to materiality. Can you speak a little about how this project emerged?

BC: I made this chair during my first year as a grad student in the furniture department at RISD. My first assignment was to make three different objects that explored three different materials: one wood, one metal, and one made up of some other “alternative material.”

I was excited to start making and wanted to hit the ground running so I spent as much time as I could in the shop messing around with machines and materials. The only issue was that I couldn’t really afford the materials to do that as much as I wanted.

I stumbled on the idea of using sawdust partially by accident when I was making a smaller piece for this materials exploration assignment. I had been in the process of learning how to use a lathe. While I was turning it on some dowels that I was playing around with, I noticed how much scrap wood was falling onto the floor. There was an entire pile of dust and chips at my feet. I was sort of fascinated by how much waste there was so I picked it all up and made this sawdust composite material that I mixed with some pigments. Then I filled in the grooves with the composite I had just made and something really interesting emerged.

I liked how this composite represented the remnants of how the thing was just made—it was something that came to be but also revealed its own process of becoming. I had made this object that contained all of these leftover parts that were taken out but then reintegrated back into itself.This was a sort of circular way of making that also became a moment of adornment on the piece which is something I also liked.

CD: So how did those early material explorations turn into a chair? Were you interested in transforming this material into a piece of furniture?

BC: I made the chair pretty soon after that. For a subsequent assignment, we were tasked with was to make a human-scale object. The problem was that I didn’t have a ton of budget to make furniture with expensive materials.

I had been dumpster diving to make other projects, and sawdust was something I could always get a lot of for free. The dowel experiments were still interesting to me, so I figured I’d continue trying to work with this material. I started with smaller-scale explorations (objects like a toaster) and worked my way up to something bigger.

At one point, I was asked to make an “ideal chair” that had to function at human scale. So I had to do it. I had to make a chair that wouldn’t collapse when you sat on it

CD: Last time we spoke, you also mentioned that part of your decision to use sawdust to make furniture came partially out of a reluctance you had to use hardwood. Can you speak more about that? What was it about the material or aesthetic qualities of hardwood that lead to this hesitation?

BC: I wouldn’t say I had a fear of hardwood per se, but I will admit that my decision to use sawdust was partially a way of avoiding hardwood as a material. I had made a couple of things out of hardwood during my undergrad. I had made a coat rack and these little disc-shaped candlestick holders out of white oak that I stained with watered-down acrylic paint. Thinking back, I can’t believe I took this nice, high-quality wood and just covered it in Home Depot house paint. Looking back at that decision, I think a lot of it had to do with my ignorance about the material (of wood) itself.

So this earlier reluctance to use hardwood had a lot to do with me finally realizing how little I knew about it, and also watching so many incredible woodworkers around me who really understood wood as a furniture-making material. At the time, hardwood just felt like this precious, loaded material that I didn’t have the skills to work with properly yet. I had a lot of respect for it, but was incredibly hesitant to use it because I knew that I didn’t quite have the tech-nical expertise to work with it well.

Now I realize that there is a meditative process that goes into working with hardwood. But it can be really slow. When I started making furniture, I wanted to make a lot and fast, and I think I had this fear that hardwood would slow me down. That has changed a lot since, and I love working with wood now.

CD: It sounds as if you felt hardwood deserved a degree of time and reverence you weren’t ready to give it yet.

BC: Yeah, I think that’s right.

CD: By using scraps and dust to make a chair, you’re bringing attention (whether intentionally or not) to the object’s materiality. You’re highlighting the waste that results from any process of making, and are also transforming something valueless into something valuable. Can you speak a little bit about waste, transformation and value? What does it mean to make something out of (basically) nothing?

BC: Something that has really inspired my thinking and making for a while now are these quilts from Gee’s Bend, Alabama. They come from this entire lineage of makers that would turn rags and scraps of clothing like old work shirts into these striking, colorful objects that are beautiful but still totally utilitarian.

I’m from Louisiana and I’ve always had this respect and affinity for these regional handicrafts and the people who make them. Gee’s Bend quilts are obviously beautiful, but they were originally made out of scarcity and out of necessity. I would consider these quilt makers artists, but the quilts they make are not just decoration. They’re also useful—they were made to keep people warm.

I’m cognizant of the fact that I have been making things in this very academic setting where there has to be a certain degree of theory and criticality that goes into my work. But I think that a lot of what I make is still rooted in the ideas and practices of this regional Southern culture.

I have this wealth of academic knowledge and in theory I also have access to almost any material I want. So it would be contrived for me to try to directly replicate what these quilt makers or other “craftspeople” are doing.

But I still think my interests share the same roots as these traditional southern handicrafts.This is why I sometimes describe my work as a type of “hard quilting.” This might sound corny, but I think there’s a huge act of love involved in making something beautiful out of waste, something out of scraps.

During my undergrad, I was also doing quite a bit of research on Gumbo, a dish that also originated from the American South. I was fascinated by the idea that it came out of the need to use table scraps. Gumbo was originally a lowly dish made up of whatever nobody else wanted to eat, and it’s evolved into one of the most iconic American food dishes ever created.

CD: There is something beautiful about these kinds of transformations that happen through sheer human creativity and resourcefulness.

BC: Definitely. I’m fascinated by this type of innate creativity. These Gee’s Bend quilts have this striking color and geometry that’s unique partially because it somehow looks so unplanned. It feels like these makers had this ingrained artistry that’s not overly planned or intellectualized. The same goes for Gumbo. Cooking is almost like improvisation—the best cooks are active in their process; making decisions and adjusting things as they go.

Improvisation and learning-by-making is an important aspect of my own practice. I like things that are made intuitively on the fly. Of course, there is always thinking and planning involved, but sometimes things are better if they are not overly intellectualized in advance.

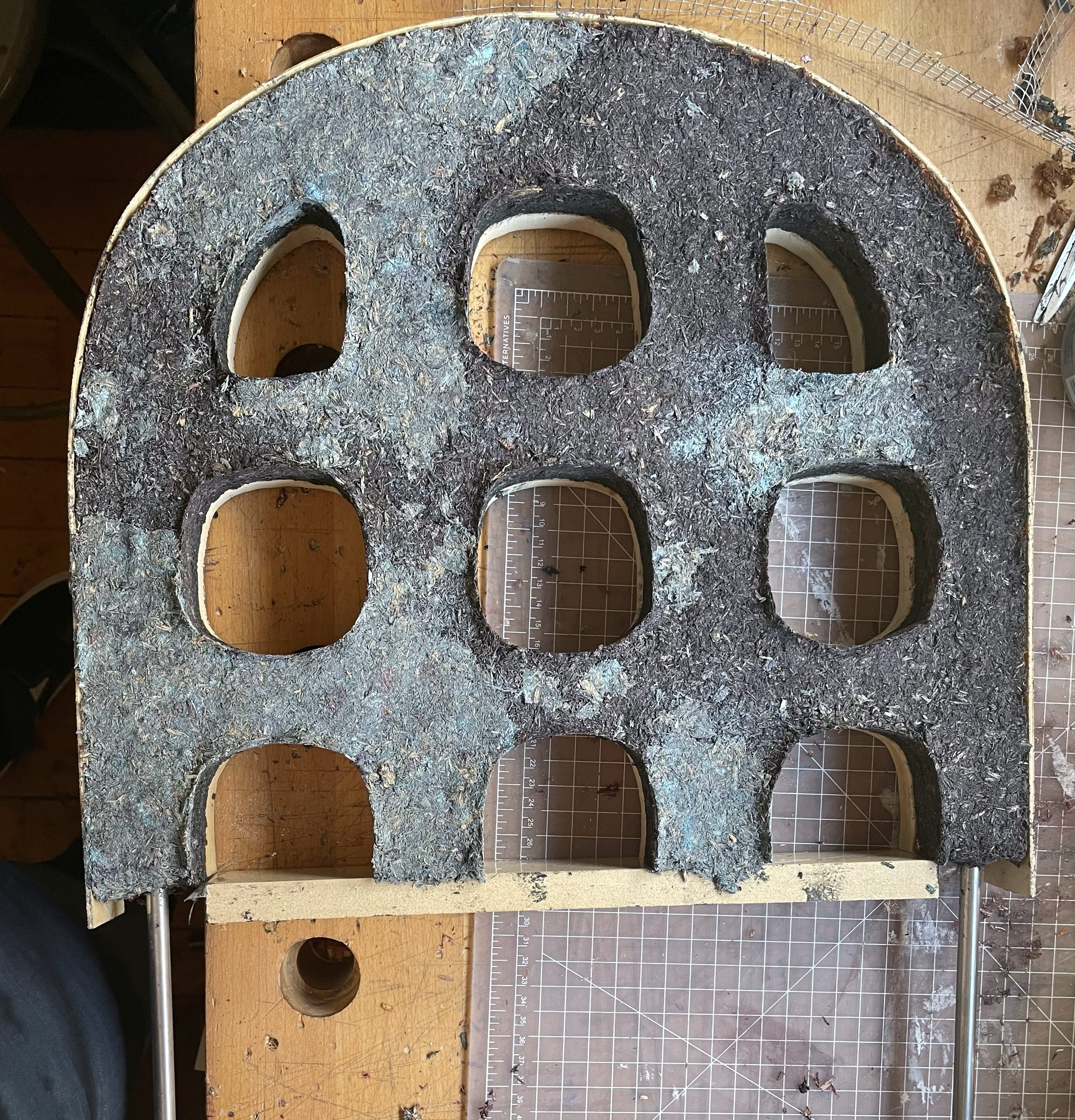

BC: The whole project was a learning process that involved experimenting with form and structure. But I’d say that one of the most improvisational aspects of the process was the application of color. The bulk of the chair is made of wood chips and glue, and then there are different pigments I integrated intuitively as I made the various components.

Throughout making the chair, I would test all kinds of different pigments from paints to dyes and would just see what would hold the color long enough and what I liked. The chair is no one single color, but a combination of different mixtures of colors and tints.

It was tricky because as I’d put each part of the chair in its mold, I wouldn’t be able to see the piece anymore until I took it out. I’d have to wait until it was dry to see how it turned out. So the color often ended up being a surprise to me. This aspect of the process was really exciting to me. And the result was a sort of intentional randomness that created its own sort of improvised cohesion.

CD: When speaking about your design process for this project, you mentioned wanting to design a system that would produce a chair. You also mentioned Tejo Remy’s “Rag Chair” as a source of inspiration. How did the “Rag Chair” influence the “Dust Chair?”

BC: A professor once asked me to name a chair whose formal qualities I liked but that also represented a particular design philosophy I was attracted to. That’s when I landed on Remy’s “Rag Chair.”

One of the things I love about it is that the chair itself feels like it doesn’t really exist in a single iteration, but is instead more like a set of instructions on how to make a chair. It’s essentially just a series of metal straps that hold together a pile of fabric. In theory, I could make that chair in my bedroom right now.

The “Rag Chair” is just a system for making a form. I’ve seen different versions of it made with old clothes, and there’s even one made out of wedding dresses. Even if you use the same types of materials to make it, no two chairs can ever be identical because of the variability of how the fabric will pill up, fold etc.

The only word I can think of to describe this variability, this approach to design, is a sort of “randomness.”

CD: This approach is reminiscent of the 60s Fluxus movement where artist would write a set of instructions, leaving the specific intepretation of each performance to the artist or spectator enacting it. While a work of art may have been performed repeatedly, it could never quite be the same twice.

BC: Right. There’s a randomness about how this chair comes to be. Whenever I make a piece of furniture, if I’m using more standard materials, where I’m sourcing the material from tends to be less important in the work. Of course, there are differences in quality, but where I get a piece of wood or metal from the store, it doesn’t really have a huge visual impact on the thing I’m making.

So the really sweet thing for me when making the “Dust Chair” was that I was able to use my classmates’ projects (i.e. their wood scraps) to make my project.

I would be like, “hey you guys, I need some dust,” and would just collect all my raw mate- rials from them. This made the whole project into something more personal and almost site- specific in a way. So although I could try to reproduce this chair, I don’t think I could make another one that’s exactly the same as the one you see here.

In theory I could make more of these, and they would fit together as a set, but no two would be identical, and it would change the nature of how the object is understood. It would become closer to regular furniture. As it exists today as a unique object, this chair feels more like an idea than just something you would sit on (even though you can).

_ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

Bill Carroll is an artist and designer currently based in Providence, Rhode Island. He’s invested in exploring a wide breadth of materials and processes, and is driven by the desire to create sincere works with rich narrative potential. His passion for making was fueled by his upbringing in New Orleans, Louisiana where he was introduced to many of his influences including improvisation, performance, quilting, and other historical processes prevalent in the American South.